| … |

Inglés.

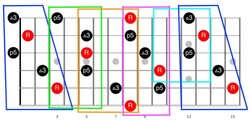

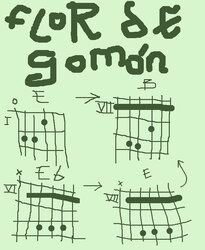

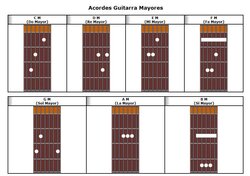

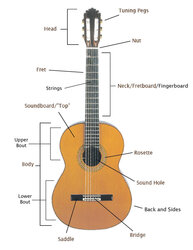

«[Well, for starters.] The parts of the guitar (image 2); starting from the top: there is the headstock, or head; the neck or arm, or fretboard; the frets; the body; the mouth, or sound hole; and the bridge. Also the notes and numbers of each string, in standard tuning. Counting from below, of the sharpest of all, is string 1, and is E; the next one is 2, and it is B; follows 3, and is G; follows 4, and is D; follows 5, and is A; follows the last one, 6, and is E, but more bass-sounding, an octave further back (I will inquire about that later). | Now, a little bit of theory. I hope you already know, about the notes or musical sounds. What it is: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Si, or maybe as I think you know them, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, being synonyms: A→La, B→Si, C→Do, E→Mi, D→Re, F→Fa, G→Sol, and these when they end, start again, but more bass-sounding, in a lower note; or more acute, in a higher note, depending on whether you ascended or descended in the order. | Almost all songs or pieces of music are made up of these notes; So, I would recommend that you learn or play the chords of these notes in their major mode, which are the most common, and the easiest ones (image 1). I'm making you a spoiler: the ways in which you place the fingers, of these chords, are repeated throughout the fretboard, and it has to do with theory, you see, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, (almost) of these notes, in between, have more notes, which are known as their versions: diesis, or sharp (#); and bemol, or flat (b), depending on whether you are reading upwards (read A, A#, B), or if you are reading downwards (reading B, Bb, A). that is, for example, A# is equal to Bb (they are actually different notes, but it is accepted in music that these two notes are equal, so as not to confuse). Now, it is known as intervals in the way of counting distances between notes, and its distance measurement is in tones, and the next way is known as the diatonic scale (image 3). The diatonic scale counts intervals as follows: the distance between A and B is one tone, but the distance between A and A# is 1/2 tone, ah~, ingenious right? So when you read A and then B, you're actually skipping one note, A#. Not all notes have 1/2 tones, such as the range of D and B, and, E and F. So, back with the chords; if you make any chord, and you run it forward (and add a bar, if you need it), you would be making that chord, but in its sharp version (#) if that chord is not E or B; And if instead of going forward, you go backwards (and also, you add a bar if you need it), you would be making that chord in its flat (b) version. Doing this once again would result in the chord that follows it, being ascending or descending from the scale A, B, C, D, E, F, G. All the fretboard has chords, you can learn which are the bar chords of the most famous positions such as: 5 fret, 7 fret, or 12 fret.

That's all I can think of right now. If you get bored from de major tones, I recomend you to take a practice of the «armonical circles of the guitar», they have many chords and variations, such as, majors, minors, and sevenths? (I don't know how it's called in english), so you can learn them, and be familiarized with them. [...]»

Español.

«[Bueno, para empezar.] Las partes de la guitarra (imagen 1); empezando por la parte de arriba: está el clavijero, o cabeza; el cuello o brazo, o fretboard; los trastes, o frets; el cuerpo; la boca, o sound hole; y el puente. También las notas y los números de cada cuerda, en afinación estándar. Contando desde abajo, de la más aguda de todas, es la cuerda 1, y es E; la que le sigue es la 2, y es B; sigue la 3, y es G; sigue la 4, y es D; sigue la 5, y es A; sigue la última, la 6, y es E, pero más grave, una octava más atrás (indagaré más adelante sobre eso). | Ahora un poco de teoría. Espero que conozcas ya, sobre las notas o sonidos musicales. Lo que es: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Si, o tal vez como creo que los conoces, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, siendo sinónimos: A→La, B→Si, C→Do, E→Mi, D→Re, F→Fa, G→Sol, y estas cuando se acaban, inician de nuevo, pero más graves, o más agudas, dependiendo si ascendiste o descendiste en el orden. | Casi todas las canciones o piezas musicales están conformadas por estas notas; entonces, te recomendaría que te aprendieras o tocaras los acordes de estas notas en su modo mayor, que son las más comunes, y las más fáciles (subiré en otra publicación los acordes, porque hay versiones que no son correctas de tocar). Te voy haciendo un spoiler: las maneras en las que colocas los dedos, de estos acordes, se repiten a lo largo del fretboard, y tiene que ver con teoría, veraz, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, (casi) todas estas notas, entremedio, tienen más notas, a las cuales se les conoce como sus versiones: sostenido, o sharp (#); y bemol, o flat (b), dependiendo si estas leyendo de manera ascendente (leer A, A#, B), o si estas leyendo de manera descendente (leer B, Bb, A). es decir, por ejemplo, A# es igual a Bb (en realidad son diferentes notas, pero se acepta en la música que estas dos notas sean iguales, para no confundir). Ahora, se le conoce como intervalos a la manera de contar distancias entre notas, y su medida de distancia es en tonos, y la manera siguiente se le conoce como escala diatónica (imagen 2). La escala diatónica cuenta intervalos de la siguiente manera: la distancia entre A y B es de un tono, pero la distancia entre A y A# es de ½ tono, ah~, ingenioso, ¿verdad? Entonces tú al leer A y luego B, en realidad estas saltando dos notas, y por encima de una, A#. No todas las notas tienen ½ tonos, como el intervalo de D y B, y, E y F. Entonces, volviendo con los acordes por fin; si tú haces cualquier acorde, y lo recorres un fret hacia delante (y le agregas una barra, si lo necesita), estarías haciendo ese acorde, pero en su versión sharp (#) si es que ese acorde no es E o B; y si en vez de recorrer hacia delante, recorres hacia atrás (y también, agregas una barra si lo necesita), estarías haciendo ese acorde en su versión flat (b). Haciendo esto una vez más, te daría como resultado el acorde que le sigue, siendo ascendente o descendente de la escala A, B, C, D, E, F, G. Todo el fretboard cuenta con acordes, puedes ir aprendiendo cuales son los acordes de barra de las posiciones más famosas como: 5 fret, 7 fret, or 12 fret.

Eso es todo en lo que puedo pensar ahora mismo, si te aburres de los acordes mayores, te recomiendo que practiques los «círculos armónicos de la guitarra», estos tienen muchas variables de los acordes, como, por ejemplo, mayores, menores, y séptimas, para que puedas aprenderlas y familiarizarte con ellos [...]»

|